_UNDERSCORE: PROUD TO BE DIFFERENT

_UNDERSCORE: PROUD TO BE DIFFERENT

On the occasion of Pride Month, which annually celebrates and commemorates LGBTQIA+ pride, we shed a light on queer films and their making in Europe.

On the occasion of Pride Month, which annually celebrates and commemorates LGBTQIA+ pride, we shed a light on queer films and their making in Europe.

by Pascal Edelmann

The vast majority of pictures we grow up with show us heteronormative realities. How do filmmakers remember when they first saw something other than that, what it was, and what that did to them?

Polish filmmaker Kasia Adamik cannot remember a specific film but points out that she “watched many films of all kinds, and often not entirely appropriate for my age. Sometimes five films a day, in a theatre or on video.” She watched PRICK UP YOUR EARS and QUERELLE, “way before I thought about my own sexuality seriously.“ Swedish director Levan Akin remembers “seeing POLYESTER by John Waters on cable TV back home in Sweden when I was 13 years old. I had never seen anything like it and I was equally shocked and excited by it”. And veteran German director Monika Treut shares her memories of seeing Fassbinder’s THE BITTER TEARS OF PETRA VON KANT: “The weird relationship between Petra and her assistant Marlene and her new love Karin opened up the “normality” of lesbian relationships,” she says, “even though these were pictured as quite problematic and sadist.” It was very important also for Czech filmmaker and activist Kateř Tureček who remembers watching BOUND, “on TV with my hardcore communist grandma, in her king-size bed with her dogs. And she loved it! I think she was pretty queer.” “As a child, the only LGBTQ film with gay characters shown on French TV was the original LA CAGE AUX FOLLES,” recalls French director Pascal-Alex Vincent: “Years later, I finally saw a gay film I could identify with, MY OWN PRIVATE IDAHO. The dark romanticism, the wonderful directing by Gus van Sant, the road, the two actors … everything appealed to me so much!”

When asked about a single film from this realm that left the strongest impression, Levan Akin picks THE COLOUR OF POMEGRANATES by Sergei Parajanov which, he says, “left a great impression on me and I return to it often. It’s a very esoteric film and it ties to my Caucasian heritage with a queer lens”. Kasia Adamik remembers seeing TRUE ADVENTURES OF TWO GIRLS IN LOVE and BOUND in the 90s as “mind blowing, because it showed that sapphic stories could be told in any genre, that they could be happy and fun or they could be cinematic dark thrillers.” “That”, she adds, “was great!“ Monika Treut also finds it difficult to single out one film but shares how Derek Jarman’s JUBILEE left a lasting impression on her: “The vicious gang of punk guerrilla girls impressed me tremendously and encouraged me to keep being rebellious.” Pascal-Alex Vincent names WILD REEDS by André Téchiné which he saw “in Cannes, as a film-student. It’s about falling in love with your straight best friend, and it takes place in the 60s, in the French countryside. I never felt so close to a movie.”

Even in today’s world, and especially outside of larger cities with a vivid queer scene where films with LGBTQIA+ content might be available in art-house cinemas, community centres or in the context of festivals, films that offer that different kind of reality can still play an important, sometimes life-changing role.

As Michael Stütz, project leader of the Teddy Award and head of the Berlinale’s Panorama section, describes: “It is a basic and necessary tool in one’s journey to find oneself – for that one needs representation or at least needs the content to form an opinion, a stance also to know where to stand in opposition.” He adds that it is, “important to have both the representation and identity politics driven films, as well as the more ambiguous works of queer cinema that hint beyond the border of the binary and representative system.“ Festival programmer Bohdan Zhuk from Ukraine states how, “heteronormative realities are usually very oppressive, so the whole world, whether it knows and admits it or not, desperately needs a queer liberation.“ He adds that, “of course, it’s important primarily for LGBTQIA+ identifying persons to see themselves on screen, to see the likes of them represented in the media, to know that they’re not alone. It is still relevant anywhere.“ Monika Treut emphasizes how “it’s important not only for young people to be enlightened about different lifestyles and choices. Young people who are insecure about their identity are starving to see role models who encourage them to find their own ways of coming to terms with their sexual and gender orientation.” Some of these young people are on board the Academy’s European Film Club: a new programme co-created by young people as a film platform and film club network across Europe for 12-19-year-olds to come together to watch and discuss European films and share their own. They say: “It’s crucial because we need to have this kind of representation available among the newest generations.” And add, “since young people will be the ones to stop discrimination and start to accept diversity.”

A great European LGBTQIA+ festival is BFI Flare in London. As assistant programmer Wema Mumma describes it on the festival website: “I may sound like a broken record saying this, but I just want to see queer Africans in all our courage – and joy. There are many who’d prefer that queer Africans remain hidden. I’d also love to see more asexual and aromantic people on screen. Basically, I’d like to see even more diverse representation.” As Kateř Tureček puts it: “It’s not just about showing a film, it’s a debate, too, a DJ set, a performance, it’s using the space for trans culture.” And they add: “The events are full of joy and most of the reactions are amazing because we bring something people don’t know. What they hear about trans people is not true. They can be safe and free at our events, too. And every time there is someone having their coming out.”

„The whole world, whether it knows and admits it or not, desperately needs a queer liberation.“

Bohdan Zhuk, Ukraine

Looking at the current state of LGBTQIA+ filmmaking in Europe and its reception, the situation, which cannot be discussed without looking at the respective general political and social situation, changes drastically depending on where you look.

Kasia Adamik states: “The mainstream in Poland, the Polish Catholic church, and the right-wing political ruling party which has a very wide reach through public media, unfortunately have been using LGBTQ+ as a scarecrow for political purposes.“ She continues: “Hate speech towards the community is common. No laws have been passed to help regulate same-sex couples or rainbow families. The situation is pretty grim, especially outside of cities and I think we are ranked as one of the most homophobic countries in the EU.“ In a country at war, this is, of course, even more drastic, as described by Bohdan Zhuk: “In Ukraine, we were forced to fight for our existence, all of us, also queer people, maybe them in particular, especially when it comes to the occupied territories in the east and the south where LGBTQIA+ people would be the first to be executed by the Russians.“

“We were forced to fight for our existence, especially where LGBTQIA+ people would be the first to be executed by the Russians.“

Bohdan Zhuk, Ukraine

He continues by explaining how this meant, “basic needs of survival, a roof above your head and having something to eat. But I believe that we chose to refuse being reduced to such basics, and we keep fighting for our rights, for human rights, which include equal rights for LGBTQIA+ people. Civil partnerships in Ukraine for instance are on top of the agenda at the moment”. Michael Stütz adds to this: “We are constantly struggling for orientation in the spaces we navigate, as individuals and as a community. Especially in times of multiple crises we can feel the conservative backlash breathing down our necks everywhere. There is an urgency for visibility, more than let’s say a few years ago, although it’s always been crucial“.

On a lighter note, Miguel Lafuente, programming co-ordinator for the Madrid International LGBTI+ Film Festival, reports of QueerCineLab, a state-wide network for non-heteronormative audio-visual development and production in Spain: “The Lab is growing successfully and last year we’ve got some funds for improving it, doing it in four different cities.” But on a European level there is no such initiative that we are aware of.

In the words of Monika Treut: “In terms of producing films with queer content it’s still harder to get funding – if it’s not just about sneaking one queer character into a mainstream film.“

“People are more scared of the unknown than of the familiar and inviting queer characters into their homes can change that.“

Kasia Adamik, Poland

Dedicated film festivals play an important role when it comes to the visibility of queer films. In many places, they offer the only cinema screenings of LGBTQIA+ films.

Michael Stütz explains the intention of the Panorama section and the whole Berlinale as, “queer films to be discovered by an array of individuals and professionals and then consequently reach a more audiences in many different corners of the world. As important as this might sound, we would not make much of a difference without the festival circuit. Most films now travel through the festival universe instead of the good old commercial theatrical release – but they still reach a lot of audiences.“

“These often grass roots LGBTQIA+ film festivals,“ he continues, “do the important groundwork of screening the films to their communities. They have the expertise for the local factors that are needed and have grown together with their audiences, they maintain community spaces that are often endangered by neo-liberal urban development schemes and often quickly disappear. Therefore, film festivals think strategically which spaces they can and want to inhabit and how they can transform them also into safer spaces for their communities. Our work becomes increasingly interdisciplinary, which is a good development to look for allies and COVID only made us more aware of the need to stick together, to achieve this.“

Wema Mumma explains: “My goal has been to put more queer Africans on screen and highlight asexual cinema as well. I am glad to say that we have representation of both this year. I was also really interested in the stories of queer elders, which are rare in my own community, and I’ve been able to explore and share this through a shorts programme I curated that highlights elderly LGBTQIA+ people around the world. It’s apparent to me that Flare takes inclusivity seriously. The festival strives to include everyone of every nationality, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation, which is what makes it such a comfortable space for me to exist in.”

Bohdan Zhuk describes the Molodist Festival as “the most prominent film festival in Ukraine and one that has always been representing queer cinema. It plays a unique role,“ he continues, “in bringing it to the local audience, both as part of the Sunny Bunny Festival and across the whole festival. I wish that it had a nation-wide reach and effect, but let’s be realistic – film festivals are definitely not for the wide masses. Even with several hybrid editions when we had a lot of the films freely available online, also LGBTQIA+ films, it is still not easy to reach and engage viewership.“

Giving LGBTQIA+ films an extra boost by honoring them with an award can also play an important role.

Michael Stütz elaborates on the Teddy Award which is annually presented in the framework of the Berlinale to award queer films in various categories: “The Teddy was created by Manfred Salzgeber and Wieland Speck to provide the films with more attention from the public, the press and the market and festival makers.

This is extremely relevant, today just as much it was back then. Films struggle for attention and an award with a 37-year-old history can make a difference when it comes to the attention a film and filmmaker will receive.

But the Teddy is not only the award ceremony and the celebration it entails. “We have a close relationship with the EFM (the Berlinale’s European Film Market) and partner for several industry events,“ Michael Stütz explains, „from panels, directors exchanges, film pitchings to one of the biggest receptions for the queer industry.

“On top of it, we are recording and archiving (see the Teddy YouTube Channel) interviews with directors and most industry sessions, which is immensely important to be able for events to be more than regular festival ephemera and actually accessible for many more people throughout the years. We want to expand more in this direction and keep writing our own history, create a living archive. Over decades, a network of queer film enthusiasts and professionals has been created and nurtured unlike at any other festival. Out of this network, the Queer Academy was born. The goal is to create an online platform, accessible to everyone, where local archives of LGBTQIA* Queer Film Festivals world-wide can be shared. The idea is there, but at the moment we do not have the resources and funds to take this to the next step – but we hope we will manage to be able to present more for the 40th anniversary of the Teddy Award in 2026.“

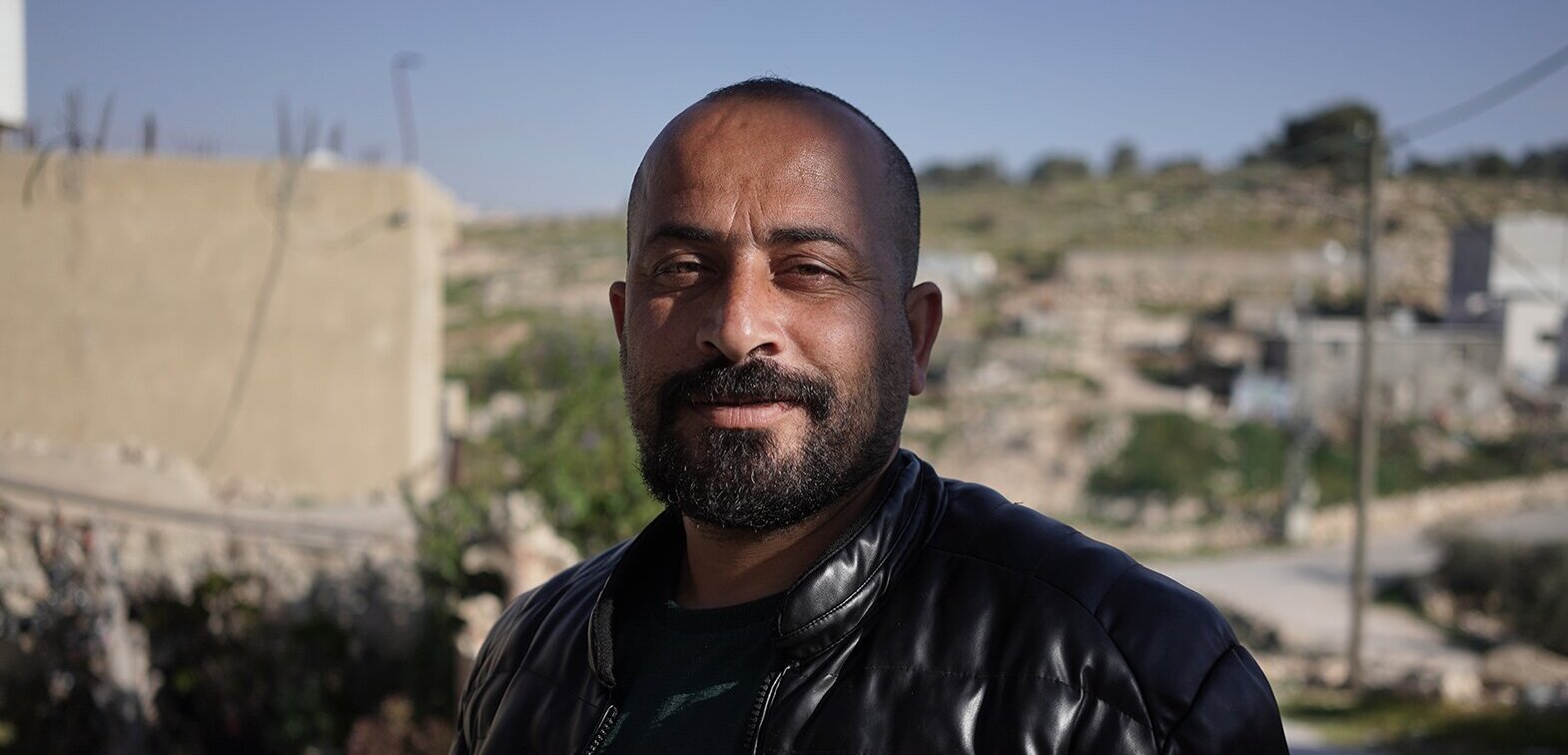

Bohdan Zhuk received a Teddy Award in 2023. This is how he describes his experience: “For a night I felt like a celebrity. It was a very touching and inspiring moment, and an honourable one for sure. On the other hand, it was triggering to be mentioned in one sentence alongside a Russian. But most importantly, it was a moving acknowledgement of my work which I’ve had the honour, the pleasure, and the privilege to do for some years, and hopefully will continue to do so. It was also an emotional moment of encouragement to keep doing it, as we announced making Sunny Bunny a queer film festival on its own. It stimulated me to launch the crowdfunding for the festival. And overall, I felt lots and lots of love and support.“

But access to LGBTQIA+ films outside of festivals is also an important aspect, where can the public see them?

Monika Treut criticises: “Showing queer films other than in smaller queer circles is still problematic. I wish we had more venues. Preserving them also needs more funding, especially when it comes to the history of queer films. Recently in Berlin the “Queere Kulturstiftung” [queer culture foundation] has been founded. We need more initiatives like this one in order to keep the heritage of queer films alive.“

Björn Koll, founder of “Queere Kulturstiftung“, explains how the foundation “organises queer film festivals in 13 (German) cities, publishes the film magazine “Sissy“ and will in the near future own Salzgeber Medien.“ Kasia Adamik points out: “Access to content is less of a problem with platforms or online for those who seek these kinds of images, but more should be played on TV so we could have this conversation in a wider forum.“ One such online platform for queer films was set up in Poland by Jakub Mróz: “We set up Outfilm in 2012 as a VOD platform dedicated to LGBT+ films and audiences. We wanted to support our theatrical distribution and to reach viewers in smaller cities and regions where our films were not present on big screens. Now the Outfilm catalogue contains almost 400 titles, and we promise at least one new film every Saturday evening.“ During the COVID lockdown, they were able to offer the software to support film festivals which had to go online. The young people from the European Film Club point out that either they “don’t have that sort of access” or they watch films “on internet platforms like Netflix, HBO and national platforms.”

Kasia Adamik adds how “film, or TV series to a bigger extent, can also help and change the way people think and view the community. I think people are more scared of the unknown than of the familiar and inviting queer characters into their homes, even if it’s only through a TV screen, can change that.“

When it comes to a film’s post-festival career, Bohdan Zhuk admits: „It’s complicated with the international films which will be presented in Sunny Bunny because for a lot of them, festival screenings are the only way for our audiences to see them. Some, of course, will hopefully appear on international or local streaming services, or maybe even get released in cinemas.“ Kateř Tureček brings in a completely different perspective: “I am not just a filmmaker but also an activist. And I am using the activism network, the communities, and spaces around the Czech Republic. And because I work in galleries too, I can use the gallery network, too, which is amazing – you have cinemas, community buildings, galleries. And together, that’s a lot of places where you show your films.”

As Michael Stütz points out: „But what remains is that once they leave an impression on an audience, it also then carries their narrative out into the streets and they get their own life that is beyond anyone’s control. If we manage to create living archives and to pass on cultural heritage from generation to generation, the films can maintain relevance and visibility beyond their festival and distribution existence.“

LGBTQIA+ is an initialism that stands for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexual, asexual and more”, where the “+” represents those who are part of the community, but for whom LGBTQ does not accurately capture or reflect their identity.

Kasia Adamik is a Polish filmmaker known for POKOT (co-directed with Agnieszka Holland), WATAHA and BARK! She is active on the Polish LGBTQ+ scene and involved with the Equaversity Foundation in a world-wide fundraising effort to benefit the LGBT+ community in Poland and neighbouring countries.

Swedish director Levan Akin shot to international fame with his 1919 film AND THEN WE DANCED which premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, became an international festival hit and won several awards, among them audience awards in Ghent, Madrid, Mezipatra, Milan, NewFest (New York) and Seville and the Swedish Guldbagge Award for Best Script.

Miguel Lafuente is programming co-ordinator for the Madrid International LGBTI+ Film Festival.

As part of their distribution company Tongariro Releasing, Jakub Mróz set up Outfilm together with his partner Leszek Maslowsk, the developer behind it. Now it’s available not only through web browser, but also by iOs, Android and Samsung smartTV apps. Jakub does acquisition, distribution, sales and promotion, and last year produced their first feature film ELEPHANT by Kamil Krawczycki.

Wema Mumma is from Nairobi, Kenya. She has just started her journey in the world of filmmaking as assistant programmer at BFI Flare in London. She also works as a writer and event manager and hopes to create more inclusivity through her work in the creative industries.

Michael Stütz is the head of the Berlinale’s Panorama section and project leader for the TEDDY AWARD. He has also been involved in numerous other festivals as guest speaker, curator and jury member.

German filmmaker Monika Treut has been making queer fiction and documentary films since the mid-80s, among them MY FATHER IS COMING (1991), GENDERNAUTS (1999) and WARRIOR OF LIGHT (2001). In 2017 she received the Teddy Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Kateř Tureček (* 1993) studied Theory and History of Dramatic Arts in Olomouc and completed their master’s degree at the Department of Documentary Film at FAMU. They are also involved in teaching and activism. For their film ILLUSION, they received a nomination in the Best Czech Documentary category at the 2018 Ji.hlava IDFF.

Director/screenwriter Pascal-Alex Vincent from France is known for FAR WEST (2003) and GIVE ME YOUR HAND (2008). He is also an expert for Asian cinema and made the documentaries SATOSHI KON: THE ILLUSIONIST (2021) and MIWA: LOOKING FOR BLACK LIZARD (2010).

Bohdan Zhuk is festival programmer for Kyiv IFF Molodist, BEAST IFF and the Sunny Bunny queer film festival. He received this year’s Special Teddy Award.

Films mentioned in the interviews:

BOUND by Lana & Lilly Wachowski, USA 1996

JUBILEE by Derek Jarman, UK 1978

LA CAGE AUX FOLLES by Édouard Molinaro, France 1978

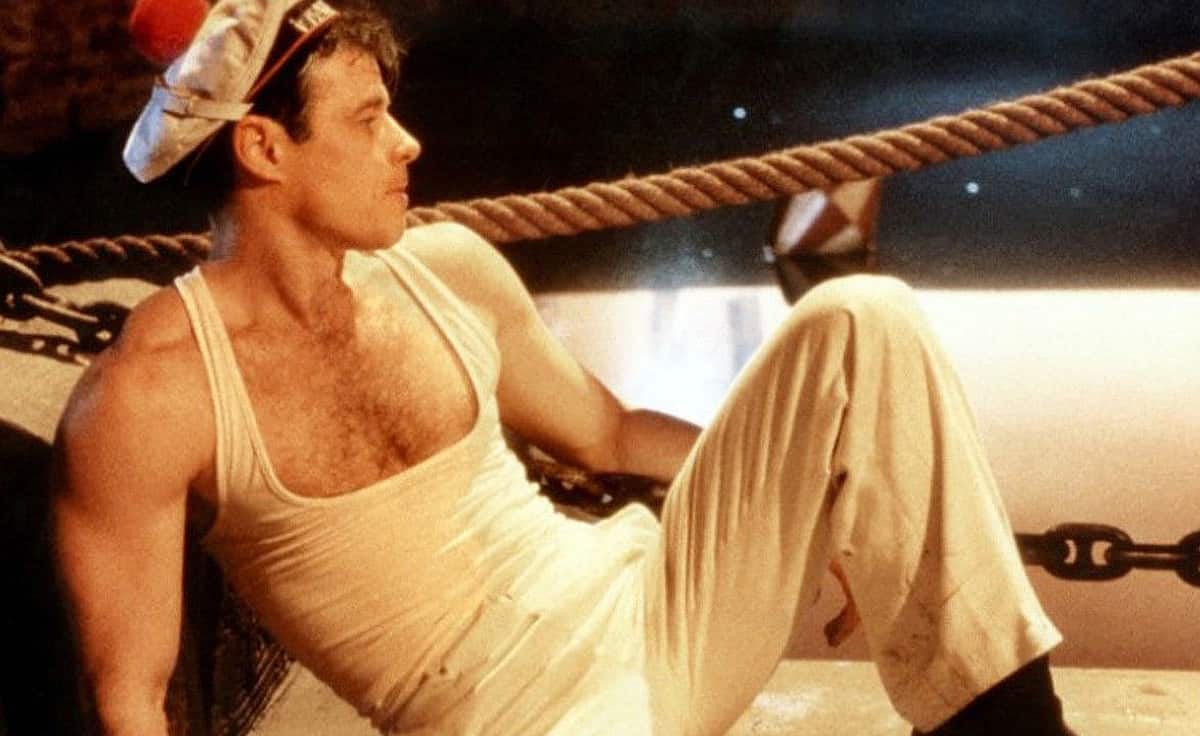

MY OWN PRIVATE IDAHO by Gus van Sant, USA 1991

POLYESTER by John Waters, USA 1981

PRICK UP YOUR EARS by Stephen Frears, UK 1987

QUERELLE by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, West Germany 1982

THE BITTER TEARS OF PETRA VON KANT by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, West Germany 1982

THE COLOUR OF POMEGRANATES by Sergei Parajanov, SU 1969

THE INCREDIBLY TRUE ADVENTURE OF TWO GIRLS IN LOVE by Maria Maggenti, USA 1995

WILD REEDS by André Téchiné, France 1994

Recommended by the interviewees:

Kasia Adamik: NINA by Olga Chajdas; PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE by Céline Sciamma, France 2019; BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOUR by Abdellatif Kechiche, France 2013; TAR by Todd Field, USA 2022; THE WORLD TO COME by Mona Fastvold, USA 2020.

Levan Akin: anything Almodóvar.

Monika Treut: My own films SEDUCTION: THE CRUEL WOMAN (1985), VIRGIN MACHINE (1988), GENDERNAUTS (1999); BORN IN FLAMES by Lizzie Borden, USA 1983; everything by Derek Jarman; the early films by Ulrike Ottinger, like MADAME X: AN ABSOLUTE RULER (1978) and TICKET OF NO RETURN (1979), early Pedro Almodóvar films like WOMEN ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN (1988).

Michael Stütz: TITANE by Julia Ducournau, France 2021; TOMBOY (2011) / PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE (2019) by Céline Sciamma; WHAT NOW? REMIND ME by Joaquim Pinto, Portugal 2013; NO HARD FEELINGS by Faraz Shariat, Germany 2020; ORLANDO, MY POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY by Paul B. Preciado, Spain 2023; plus the films by Monika Treut, Rosa von Praunhelm, João Pedro Rodrigues, Claire Denis, Isaac Julien, Derek Jarman, Ulrike Ottinger, Chantal Akerman and many many more!!

I would also add the importance of experimental cinema and video work that very early on questioned patriarchy and aesthetic conventions and very much influenced many filmmakers.

Bohdan Zhuk: It’s an impossible task to limit such a list, or any of such kind. Instead, I’m just going to recommend one filmmaker, Kira Muratova. She wasn’t queer herself (that we know of at least) but her films are deeply queer even when not touching LGBTQIA+ subjects (which was rare and happened in her later films, when Ukraine was already independent and not under Soviet censorship that didn’t allow her to make films at all). She is one of the greatest filmmakers in the history of cinema, and one of the least known.