THE INVISIBLE FIGHT

THE INVISIBLE FIGHT

THE INVISIBLE FIGHT

NÄHTAMATU VÕITLUS

Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Finland

SYNOPSIS

USSR-China border, 1973: Young soldier Rafael is on guard duty when the border falls under attack from flying Chinese kung fu warriors, leaving him as the sole survivor. Utterly fascinated by the long-haired martial artists who easily dispatched his fellow guards, all while blasting forbidden Black Sabbath music from their portable radio, Rafael is struck by a revelation: he too wants to become a kung fu warrior. Looking for mentorship but with limited options, faith leads Rafael to seek martial arts teachers at the most unlikely of places: the local Eastern orthodox monastery, where the black-clad monks begin his training. With a sceptical mother, a rival monk, and a budding love interest pulling him in different directions, Rafael finds that his journey to unlock the greatest martial art of all – the almighty power of humility – is long, winding, and full of kick-ass adventures.

CREDITS

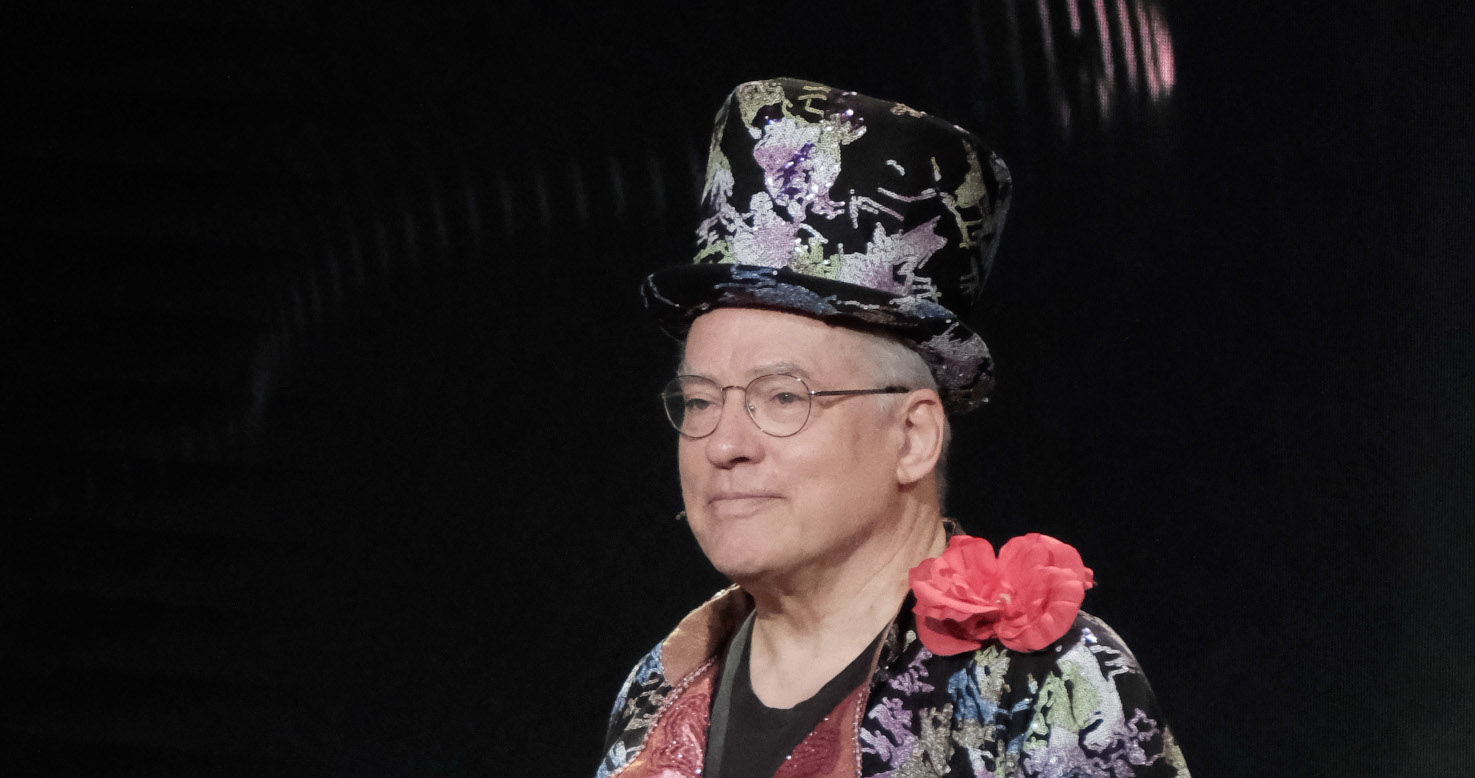

Written & directed by: Rainer Sarnet

Produced by: Katrin Kissa, Amanda Livanou, Alise Gelze, Helen Vinogradov, Aleksi Bardy

Cinematography: Mart Taniel

Editing: Jussi Rautaniemi

Production Design: Jaagup Roomet

Costume Design: Jaanus Vahtra, Berta Vīlipsone

Make-Up & Hair: Anu Konze

Original Score: Koshiro Hino

Sound: Janne Laine

Visual Effects: Antonis Kotzias

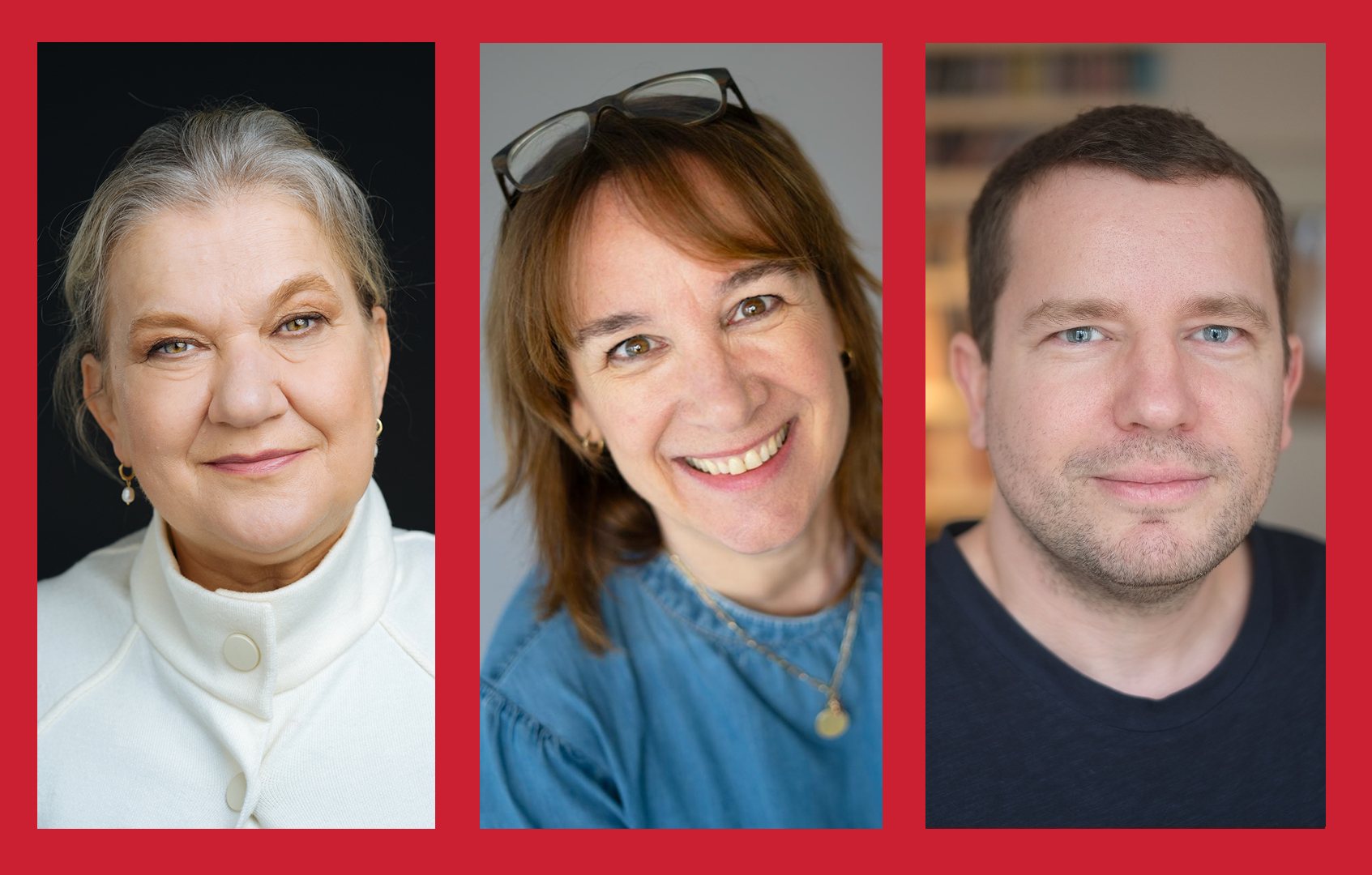

Cast: Ursel Tilk (Rafael), Ester Kuntu (Rita), Kaarel Pogga (Irinei), Indrek Sammul (Nafanail)

STATEMENT OF THE DIRECTOR

It all started when I brought my friend in the hospital a book called ‘Not of This World’. It contained real life stories of two orthodox monks who both died young. The gift was meant to be taken with black humour – we are both fans of decadence. The friend proposed an idea: to make a movie about monks. So, he kind of gave me a present in return.

The story that stood out for me in the book, spoke about a young monk, Father Rafael, who was active in the Soviet Union in the Seventies, in the monastery in Pechory. I began to explore the era, and it turned out that many young Russian monks were ex-hippies. There was a resistance to the material world, and, as hippies, orthodox monks wear their hair long, have black clothes, and there are skulls in the catacombs. You might say that their universe seemed quite rock’n’roll to me. Exploring Father Rafael’s life, it came out that he had served in the army near the Chinese border, his military unit was attacked by Chinese bandits, and he alone survived. At that point, the thought of adding kung fu emerged: Rafael sees the Chinese use it while in the army and is inspired to learn. Just as religion, martial arts were forbidden in the Soviet Union. So, it’s a sort of double rebellion. I also chanced upon a website called ‘Death to the World’, run by an ex-punk orthodox monk. There was a line: the last true rebellion is the monastery. So that kung fu, Black Sabbath, and the monastery are joined together by rebellion.

When I met the monks for the first time, I was very surprised by their humour. A sense of the absurd, even. As one monk said, without a sense of the absurd there is no way to put earth and heaven together. I discovered a lot of joy in monastery. Not artificial joy, but the real one. Orthodoxy has been called the faith of the heart. There is very little that is scholastic, or rational. Heart leads the way, emotions, love and beauty.

I do not like missions in real life, and I don’t think this topic is much of a taboo that cannot be discussed. Religions have disgraced themselves, no question there. But who’s to blame? This is who we are. I am a Christian, too, and I disgrace myself constantly. But the church is not an institution where you have a contractual relationship; some paper that you have to respect, or you will get fired. No-one can live without fault. The main activity is inside, the invisible fight. We rise, we fall, and rise again.

In religion, I was not drawn so much to the teachings, but the sensory experience. Music and beauty, icons, liturgy, that I really relish. You are more connected with it by a sensory state than reason. Psalms are read in singsong; the words of the scriptures have divine energy that works even if you don’t hear everything or understand it. It is not the word of God by reason, but by saturation with the divine spirit.

I knew from the beginning that I cannot make a serious film about monks. I felt that it doesn’t fit the theme, at least not according to my own experience. In the Pechory monastery, we had a lot of laughs. The pilgrims are weirdos as well. We laughed ecstatically at times.

“Without humour, things don’t work”, an old Russian man said to me in church. There is no consensus to be achieved with humour, we don’t all need to laugh unanimously at something, and be all serious about something else. Playing the fool has other objectives. In Russian Orthodox, there is a tradition called Yurodivyi – A Fool-for-Christ. Yurodivyi is a holy madman who expresses his faith in an untraditional way. This kind of expression brings forth a lot of things that the reasonable mind couldn’t capture. Hamlet acted mad too, to find out the truth.

Playing a fool is an ancient artform, because it unlocks something in the human essence that we keep hidden all the time. Our imperfection. Religion has a very adequate and relaxed attitude towards human imperfection. Religious thought and art have the same effect on me as the absurd or surrealism. The undefinable aspects are commonplace. Suffering and death are taken lightly, even with joy. It provides peace of mind in difficult situations, but without rose-tinted glasses. Christ is full of contradiction, and this is captivating.

- Feature Film Selection 2024